Lab 1: Computer Networks

This lab offers a very brief overview of what could be (and often is, in college-level CS) a full course in itself: how the Internet works. It emphasizes a few key ideas:

- The Internet is a huge artifact, built and maintained by thousands of people around the world, based on a level of cooperation that's remarkable, considering that it connects enemy countries and competing corporations.

- The design of the network has to be very different from the kind of programming students have done in this course, because in such a large system you have to assume that some network software or (more likely) equipment will fail in the middle of a transaction. So the network needs a lot of redundancy, and software (mostly running in routers) has to manage the redundant parts.

-

The complexity of the network is such that abstraction is an absolute requirement, not just a good idea in general. The multiple levels of abstraction are provided by protocols: design specifications for software in terms of the services it can expect from lower levels of abstraction and the services it must provide to higher levels. There are four main levels of abstraction:

- Application layer: User-visible software such as browsers and email. Assumes a reliable Internet.

- Transport layer: Provides the abstraction of a reliable Internet. The main protocol at this level is TCP: Transmission Control Protocol. Assumes a world-wide addressable Internet.

- Internet layer: Provides the abstraction of a world-wide Internet. The main protocol at this level is IP: Internet Protocol. This runs mainly in routers, not in users' computers. Assumes connection to a local network and one or more larger networks.

- Link layer: Provides hardware connection to a network. Ethernet, WiFi, and cellular data are the main examples.

- The running of the Internet takes a lot of work, and involves a lot of international politics. "Who's in charge?" is not a simple question.

In addition to these main points, there's a lot of vocabulary the College Board expects students to learn. We try to present the vocabulary a little at a time, in contexts in which each term makes sense.

Pacing

The 4 lab pages could be split across 2–4 days (

80–160 minutes). Expected times to complete follow:

Lab Pages

-

Page 1: What Is the Internet?

-

Learning Goals:

- Understand the range of uses of the Internet, including but not limited to the World Wide Web.

- Understand some of the technical requirements to make the Internet work.

- Understand what it means for data or processors to be "in the cloud."

-

Tips:

- Ask your school's IT person if you can run "traceroute" in class, to show students how a message is routed to a computer in another country.

-

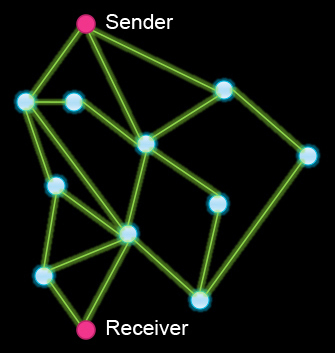

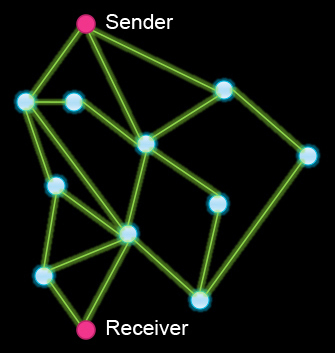

Page 2: Network Redundancy.

- Learning Goal: Understand how network redundancy is accomplished on the Internet.

-

Tips:

-

After students have worked through the questions on the lab page, you could use these questions for a group discussion:

- Are there any other two nodes whose failure would stop the message from going through? Either the two neighbor nodes of the receiver could fail or the right neighbor node of the receiver and the node above the left neighbor node of the receiver could fail.

- What is the minimum number of extra connections you'd have to add so that any two nodes could fail without preventing messages between any two other nodes? The answer is two. There are four vertices with only two neighbors; use one edge to connect any two of those, and another to connect the other two. (This will require "crossing" connections on the graph as it is drawn here, but this is OK and could offer an opportunity to remind students of what the elements of the graph represent.)

- What is the minimum number of nodes that can stop working before the sender and the receiver can't communicate? One way to answer this question is to note that the receiver has only two neighbors, so if those two nodes go down, it can't get any messages no matter where the sender is in the network. (The same argument applies to the sender, but since the sender has three neighbors and 3 > 2, it's the receiver that provides the answer to this question.)

- What is the maximum number of nodes that can fail and still let Sender and Receiver communicate? To answer this question, you can find the shortest path between the desired endpoints (which is the one through the two highly-connected central nodes) and then let all the other nodes fail.

- The last question on this student page poses several questions. Here are some possible correct responses:

- The benefit of fault tolerance is that if some piece of the system fails, the whole system doesn't fail.

- The Internet is fault tolerance because is has redundent connetions.

- The vulnerablilities to failure include damage to a cable, power failure, military intervention, hardware malfunction, etc.

-

Page 3: Internet Abstractions and Open Protocols.

-

Learning Goals:

- Understand the four layers of abstraction in the Internet protocols.

- Understand how TCP/IP together provide the main abstractions for the net.

- Understand how your home router can send a message to any IP address.

-

Tips:

- The Wikipedia article "Internet Protocol Suite" has a chart showing just a few of the 300-odd protocols that run the Internet. You might let interested kids read up on some obscure protocol and explain to the class what it does and why it's important.

- The specific implementation of TCP/IP most commonly used around the world was developed at UC Berkeley. :-)

- It's easy to give a one-sentence description of a protocol, but, for example, early implementations of TCP worked in theory but could easily become swamped with backed up traffic; the current protocol description includes complicated timing mechanisms that are essential to keeping the net flowing smoothly.

-

Page 4: Who's In Charge of the Internet?

- Learning Goal: Understand the history of the development of the Internet. In particular, understand the political history of ICANN and the IETF.

Are we cutting these assignments? If so, please delete HTML. --MF, 5/16/20

Solutions

Correlation with 2020 AP CS Principles Framework

Computational Thinking Practices: Skills

- 1.D: Evaluate solution options.

- 5.A: Explain how computing systems work.

Learning Objectives:

- CSN-1.A: Explain how computing devices work together in a network. (5.A)

- CSN-1.B: Explain how the Internet works. (5.A)

- CSN-1.D: Describe the differences between the Internet and the World Wide Web. (5.A)

-

CSN-1.E: For fault-tolerant systems, like the Internet:

- Describe the benefits of fault tolerance. (1.D)

- Explain how a given system is fault-tolerant. (5.A)

- Identify vulnerabilities to failure in a system. (1.D)

Essential Knowledge:

- CSN-1.A.1: A computing device is a physical artifact that can run a program. Some examples include computers, tablets, servers, routers, and smart sensors.

- CSN-1.A.2: A computing system is a group of computing devices and programs working together for a common purpose.

- CSN-1.A.3: A computer network is a group of interconnected computing devices capable of sending or receiving data.

- CSN-1.A.4: A computer network is a type of a computing system.

- CSN-1.A.5: A path between two computing devices on a computer network (a sender and a receiver) is a sequence of directly connected computing devices that begins at the sender and ends at the receiver.

- CSN-1.A.6: Routing is the process of finding a path from sender to receiver.

- CSN-1.A.7: The bandwidth of a computer network is the maximum amount of data that can be sent in a fixed amount of time.

- CSN-1.A.8: Bandwidth is usually measured in bits per second.

- CSN-1.B.1: The Internet is a computer network consisting of interconnected networks that use standardized, open (nonproprietary) communication protocols.

- CSN-1.B.2: Access to the Internet depends on the ability to connect a computing device to an Internet-connected device.

- CSN-1.B.3: A protocol is an agreed-upon set of rules that specify the behavior of a system.

- CSN-1.B.4: The protocols used in the Internet are open, which allows users to easily connect additional computing devices to the Internet.

- CSN-1.B.5: Routing on the Internet is usually dynamic; it is not specified in advance.

- CSN-1.B.6: The scalability of a system is the capacity for the system to change in size and scale to meet new demands.

- CSN-1.B.7: The Internet was designed to be scalable.

- CSN-1.C.1: Information is passed through the Internet as a data stream. Data streams contain chunks of data, which are encapsulated in packets.

- CSN-1.C.2: Packets contain a chunk of data and metadata used for routing the packet between the origin and the destination on the Internet, as well as for data reassembly.

- CSN-1.C.3: Packets may arrive at the destination in order, out of order, or not at all.

- CSN-1.C-4: IP, TCP, and UDP are common protocols used on the Internet.

- CSN-1.D.1: The World Wide Web is a system of linked pages, programs, and files.

- CSN-1.D.2: HTTP is a protocol used by the World Wide Web.

- CSN-1.D.3: The World Wide Web uses the Internet.

- CSN-1.E.1: The Internet has been engineered to be fault-tolerant, with abstractions for routing and transmitting data.

- CSN-1.E.2: Redundancy is the inclusion of extra components that can be used to mitigate failure of a system if other components fail.

- CSN-1.E.3: One way to accomplish network redundancy is by having more than one path between any two connected devices.

- CSN-1.E.4: If a particular device or connection on the Internet fails, subsequent data will be sent via a different route, if possible.

- CSN-1.E.5: When a system can support failures and still continue to function, it is called fault-tolerant. This is important because elements of complex systems fail at unexpected times, often in groups, and fault tolerance allows users to continue to use the network.

- CSN-1.E.6: Redundancy within a system often requires additional resources but can provide the benefit of fault tolerance.

- CSN-1.E.7: The redundancy of routing options between two points increases the reliability of the Internet and helps it scale to more devices and more people.

-

IOC-1.B.1: Computing innovations can be used in ways that their creators had not originally intended:

- The World Wide Web was originally intended only for rapid and easy exchange of information within the scientific community.

Brian

This is new. I pulled it off the bottom of the student page and dumped it here. --MF, 11/18/19