Secret Keys

Caesar Ciphers and Substitution Ciphers

On the previous page (or at some point in your life), you probably used a substitution cipher to encode your message. Perhaps you just shifted each letter of the alphabet by a certain number (like 4):

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

WXYZABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUV

That's a Caesar cipher (named for Julius Caesar).

Or you may have substituted letters without keeping them in alphabetical order, like this:

ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ

PQVFUBZOTHWYELIXRNAMGDSCKJ

That's a general substitution cipher.

- The second cipher may seem better, but there's a tradeoff. The recipient of your message has to have a way of decoding your message. If you are a king and you send a messenger to deliver your secret message, why might you prefer a Caesar cipher to a substitution cipher? What are some ways you could make the substitution cipher a more secure alternative to use?

- It turns out that even a general substitution cipher is relatively easy to figure out because certain letters in our language are used more frequently than others. You might have used this idea to break your partner's code on the previous page.

Better methods of encryption

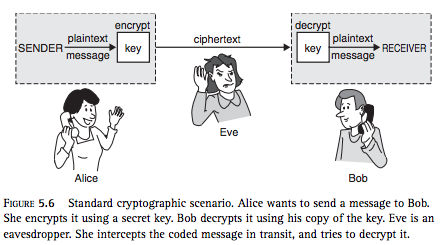

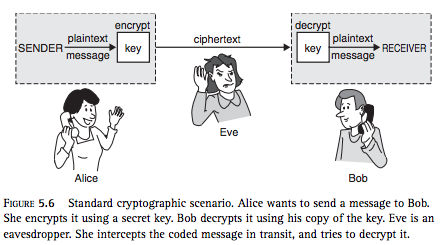

There are many other methods of cryptography. Many of them follow the pattern shown in this image (taken from Blown to Bits page 171).

- This picture shows a way that Alice and Bob might send a message that Eve doesn't understand. Could this picture work if Bob is actually an online company and Alice is sending her credit card number? Discuss how this picture might or might not work in such a situation.

- Read "Secret Keys and One-Time Pads" (Blown to Bits pages 169-173) to learn about Vigenere ciphers and methods used during World War 2 and the Cold War.