Comparison with CSP Framework

Computer programming can be immensely satisfying. You get to be inventive and creative. Programming gives you a kind of authorship and control that's quite beyond what people mostly can get in other activities. It's what Seymour Papert called "hard fun," fun precisely because it is mind-stretching but still under your own control. And, because you can judge correctness yourself—your program either works the way you want or it doesn't—you become the judge, not the judged. If the program doesn't work, it's not a failure but a work in progress; you fix it, alone or with ideas from others. If it does work, you may still want to embellish it with new ideas or more elegant structure. That view of learning—that one can always fix what needs fixing and improve what's already good—and the sense of authority that one gains by being a creator are known to be valuable to kids (and adults). And, of course, the skills and ideas behind programming—the computer science of it—are valuable. Programming is a game of skill, like chess but without the competitive aspect, and with useful results beyond the act of programming itself. These reasons, alone, are enough to make us want all kids to have the opportunity to experience the joy of programming.

Given the chance to learn, programming can also be accessible to many students who have not had success in areas they associate with computers and mathematics and science, or who do not picture themselves as programmers. Precisely because you can see for yourself how your program is behaving, you are in a better position to know what steps to take to improve it than you are in most other subjects.

And, increasingly, computer science and the ways of thinking and opportunities to create that it opens up, are also a matter of equity. Learning to program doesn't guarantee a job but it certainly widens the field of choices a student can make.

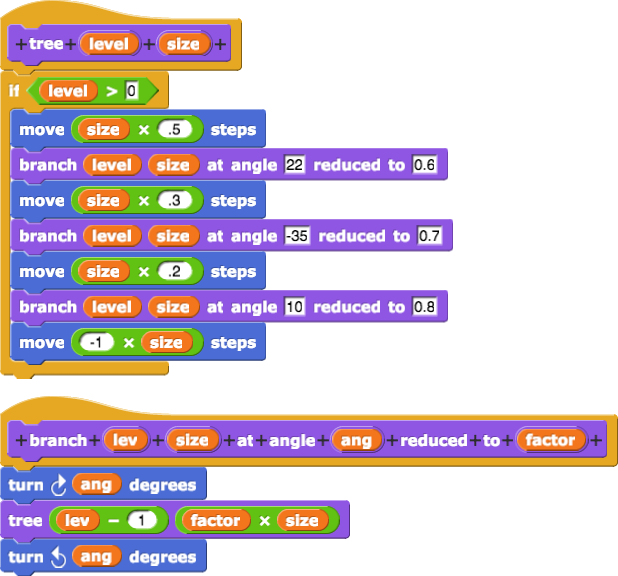

The designers of BJC also think that computer programs, and not just the pictures and apps that programs can produce, can be things of beauty. Programmers, like mathematicians and writers and engineers, develop a sense of esthetics. This is one reason why we decided to include some topics—in particular recursion—that go beyond the CSP requirements. A recursive program can generate a complex, intricate computing process from a very small piece of code. For many of us who learned to program, that was the revelation that stands out as the moment when we discovered the beauty of programs.

Preserving the beauty and joy for your students takes thought. Too much scaffolding in a project and the joy and sense of creative power is gone; too little scaffolding and the student can feel helpless and incompetent. We tried to strike a good balance in the student materials but you will, of course, need to make your own sensitive decisions. Each page of the student materials and teacher guide has a feedback link to let you help us make the curriculum work better for you.

Computer Science Principles

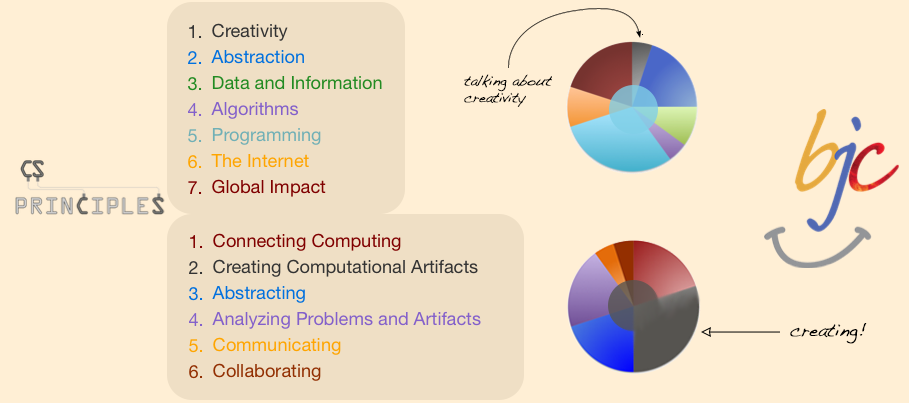

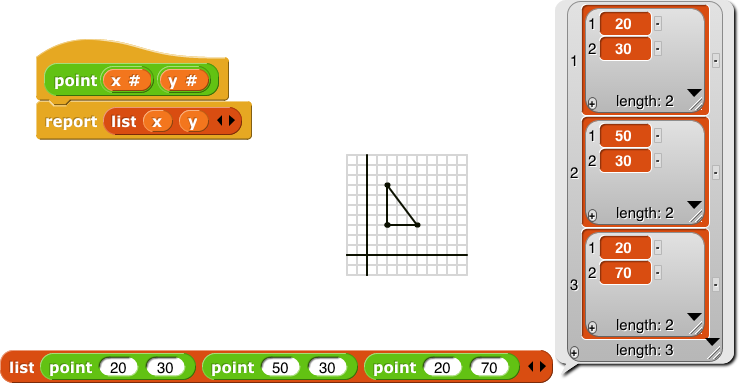

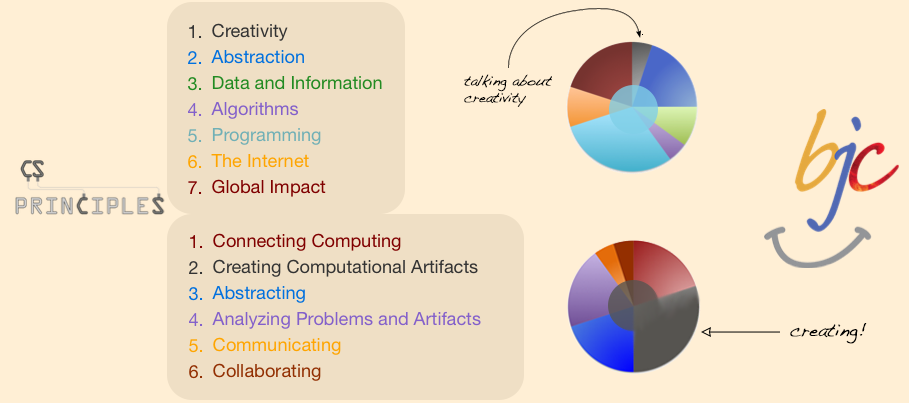

The College Board AP CS Principles curriculum framework is organized around seven "Big Ideas" (things to learn) and six "Computational Thinking Practices" (things to do):

Every conforming curriculum must teach all of these, but curricula may differ in the amount of emphasis given to each. (The slices in the pies aren't really quantitative, just a suggestive snapshot of how BJC stands out.)

There is much overlap between the Ideas and the Practices. Creativity is an Idea, but Creating is a Practice; Abstraction is an Idea, but Abstracting is a Practice. Think of the first pie as representing text in the curriculum materials and the second pie as representing how we expect students to spend their time. The circles at the center of each pie indicate that the idea of Programming and the practice of Creating are at the center of BJC, and intersect with all the others.

First, the Big Ideas. BJC is proudly Programming-heavy. Snap!, the programming language we use, combines the ease of use of visual programming with expressive power previously found only in the most sophisticated text-based languages. (More on this below.) We believe that this combination helps to make programming and powerful ideas inviting and accessible to a diverse audience of beginners, who may initially not think they're interested in programming. BJC goes well beyond the CS Principles requirements, featuring the advanced techniques of recursion and higher-order functions.

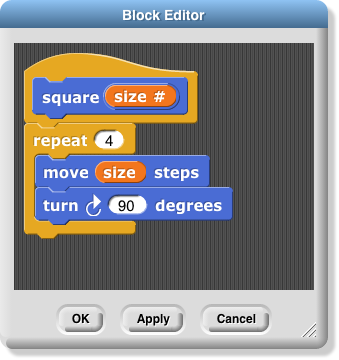

We view Abstraction as the central idea of computer science. We emphasize the use of abstraction in the context of programming. This includes both control abstraction to generalize programming patterns and data abstraction to isolate the implementation of an abstract data type from its use.

Our secondary emphasis is on Global Impact, the social implications of computing. Every unit of BJC uses readings and classroom discussion to explore various aspects of this topic. Details of the topics and teaching goals are below.

Two of the remaining four topics are more implicit than explicit in our approach. Students exercise Creativity in their programming projects, but we don't talk about it to the same extent as the other topics. Similarly, students develop Algorithms as they program, but we don't often treat algorithms as a separate topic, except when we are teaching about analysis of algorithms and asymptotic orders of growth.

The final category of topics, Data and the Internet, are important and are covered thoroughly, but where possible our coverage takes the form of programming activities rather than, for example, using commercial database software.

Now, about the Practices: The phrase "Computational Artifacts" is meant to encompass videos, slide decks, blogs, programs, music, spreadsheets—anything you can create with a computer. We treat creating as the most important of the Practices. And we see computer programs as the most important artifact students will create because, when a student writes a program, two acts of creation happen at once. The student is interested in the product—a game, for example—and displays creativity in the design of that product. But she creates the game by creating a program, and also displays creativity in the design of the program structure. The latter is the real computer science.

Just as the idea of abstraction is central to, and inseparable from, the idea of programming, the practice of abstraction is central to programming. We constantly encourage students to use layers of abstraction to structure a programming project.

"Connecting computing" can mean connecting it to hobbies, or connecting it to industry, or to science. But most importantly, for us, students connect computing to its social implications, our other main focus.

Almost as important is the practice of analyzing programs: debugging, predicting the behavior of someone else's code, and thinking about efficiency. But we would emphasize that this skill is not an end in itself; it serves the ultimate goal of creating programs that work.

The two remaining practices—communicating and collaborating—are important precisely because they are not unique to computer science. Like most CSP curricula, we use pair programming, so students are constantly talking with their partners and sharing the work. At the beginning of the course we teach the process of pair programming, and in the discussion of social implications of computing students have to communicate their ideas. Students are constantly engaging in these practices, but BJC doesn't talk about them very much.

Visual Programming

Snap!, the programming language designed to support this course, uses the Scratch design of drag-and-drop blocks but adds power that is essential for developing advanced ideas and programs.

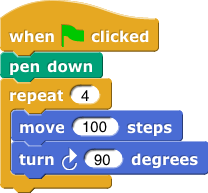

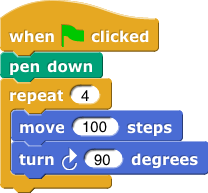

The visual metaphors of the Scratch design give it a very low entry threshold, which is why it is routinely learned by self-taught eight-year-olds. The shapes and colors remind users of the block categories.

The C-shaped block is a loop, and visually encloses the code that should be repeated. Green blocks are about drawing; blue blocks are about motion.

But because Scratch was designed to be usable by eight-year-olds, its designers left out some key capabilities for teaching computer science. Snap! adds the needed abstraction capabilities, while preserving the carefully designed visual metaphors to aid understanding:

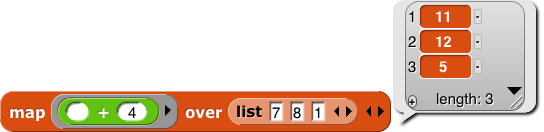

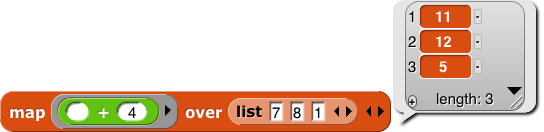

Because Snap! blocks can take other blocks or scripts as inputs, and because of the very simple notation used for anonymous functions, we can teach the even more powerful control abstraction of higher-order functions:

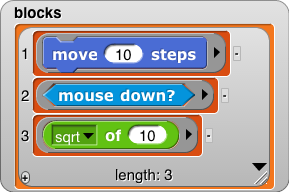

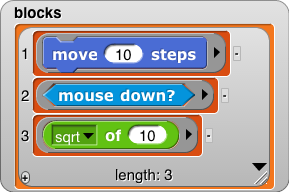

This capability, first class procedures, makes Snap! more powerful and expressive than most text-based programming languages. The visual representation makes procedure as data seem concrete to students, as in this list of procedures:

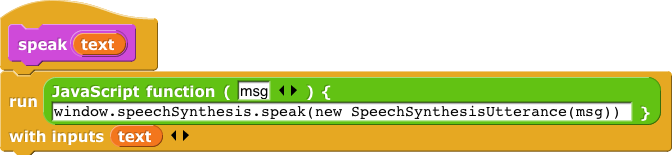

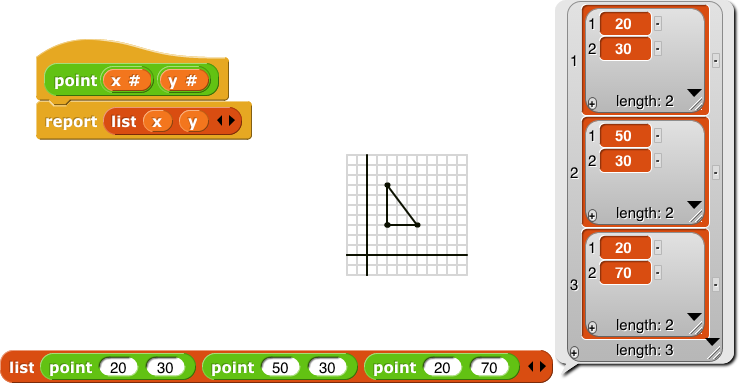

Finally, because lists are first class data in Snap!, we can build abstract data types and use them in larger data structures, such as this triangle:

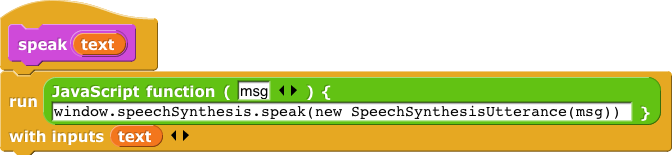

Snap! also provides access to the Javascript environment in which it is implemented.

(The picture shows a one-liner, but there is no limit to the length or complexity of the Javascript function defined by the block.) With this capability we can have our cake and eat it too, with respect to the (pointless, we think) argument about block languages vs. text languages. We don't teach Javascript in BJC, but it's available as an enrichment activity if desired.

Also, because Snap! runs in any modern browser, students can make mobile apps for iOS or Android by putting a shortcut to the project's URL on the device's desktop. From the browser we can't access phone-specific information such as contact list or GPS position (standalone versions are in the works), but things like video game projects work fine.

Snap! also connects with several robots and sensors (Finch, Hummingbird, Sphero, Lego NXT, Wiimote, LEAP Motion, Arduino, etc.) by way of small applications installed on the local computer.

Social Implications of Computers

Here are the topics included in the BJC units:

- Privacy and Search Engines

- Video Games and Violence

- Owning Ideas (Copyrights and Patents)

- Encryption

- Innovation

-

Computers and Community

- social networks

- cyberbullying

- Computers and War

- Computers and Work

|

|

We take the stand that any technology has risks and benefits, and that people decide how to minimize risks and maximize benefits. Therefore, in each topic, we have students evaluate alternate points of view. For example, rather than shut down debate on the downloading of copyrighted works (e.g., music), which many students do, we try to open the issue by eliciting honest perspectives on both the value and harm in it, and whether there are ways to protect the value and remedy the harm (e.g., by considering alternate ways to support artists and writers). Both student pages and the Teachers' Guide point to provocative readings on each topic.

In general, we hope to leave students feeling optimistic about the benefits of technology, but also ready to think critically about any specific technology. We also remind them that the decisions about how a new technology is used are made by human beings, including themselves if they pursue a career in computer science, so they shouldn't feel helpless in the face of a supposed technological imperative.

We use the excellent Blown to Bits as the textbook for this part of the course. (There is no textbook for the technical parts of the course, beyond the online materials we provide.) The book is aimed at adult readers, and will be difficult especially for ESL students, so we use short excerpts and discuss alternative presentations in the Teachers' Guide. Like the rest of the course materials, this book is available free online, with a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA license.

The book is a few years old now, so we supplement it with current readings, looking for topics that will be relevant to students. Students choose their own topics to study in more depth; this is one way we appeal to a diverse audience. We start class meetings with "Computing in the News," presenting items from that morning's newspaper, one generally positive and one problematic. After some teacher-chosen examples to illustrate the idea, we encourage teachers to assign the selection of articles to students in rotation.